Growing Positively

Teachers, coaches, parents and guardians are responsible for providing children with a positive and safe learning environment. There are, however, instances where physical and mental violence is perceived as a “tool” for teaching, despite the risk of causing severe and long-lasting effects on the younger generation.

Malaysia, according to a report by the End Corporal Punishment global initiative last year, is one of the 15 nations that did not fully prohibit corporal punishment in any setting, including as a sentence for crime.

The mindset of education with violence will continue to plague our community if no forms of nationwide enforcement are being implemented or considered. Violence in our educational institutions creates a hazardous environment for children and also harms their mental and emotional well-being.

Violence, said Sunway University School of Medical and Life Sciences associate dean (International) Prof Alvin Ng Lai Oon, is never the answer when it comes to educating because psychological safety plays a huge role in a student’s overall well-being.

According to Prof Ng, physical punishments such as slapping may be perceived as abuse.

The psychological effects of such acts of abuse by educators could vary from insignificant to potentially traumatic, depending on the student.

“Some may see it as the teacher trying to improve student performance, and thus the students would try harder to improve themselves, while other students may start blaming and rejecting themselves,” he said, adding that students could also perceive it as a form of acceptance or attention that they have been craving for.

Although the purpose of punishment is to discourage certain kinds of behaviour, it fails to indicate what specific action is required of the individual or how one can improve, Prof Ng explained.

“Punishments also cause negative side effects such as fear, anger, resentment, shame and guilt,” he added.

Teach For Malaysia (TFM) research, design, and impact manager Sawittri Charun said the community can no longer afford to be uninformed about the damage violence and aggression in education causes.

“The stakes are too high, and our students will be paying the price if we continue to think that fear and aggression are the best way to get students to change their behaviours,” she said, stressing that violence includes physical, verbal and emotional abuse.

A positive approach

Educators should guide students when it comes to dealing with mistakes instead of punishing them, said Universiti Teknologi Mara (UiTM) senior lecturer Dr Khadijah Said Hashim.

“The best way to guide is through discussions.

“Ask them why the mistake was made and how they can learn from it by giving positive, constructive feedback.

“When it comes to children, you need to give room for them to explain and justify their mistakes; they have so many things in their minds, so you don’t know if they’re struggling with something because, at the end of the day, they’re human too,” she added.

Khadijah said allowing children to talk about their mistakes would also motivate them to be better because they feel heard.

“If you let them express their thoughts and feelings, they will feel better about themselves.

“Sometimes, children learn more about themselves when they get to identify what they did wrong and why they did it.

“Educators should take the opportunity to share their thoughts on how these children can improve and do better the next time around.”

In order to achieve this, educators must have a growth mindset and believe that values and virtues can be developed as they are not necessarily innate.

Universiti Utara Malaysia School of Education senior lecturer Dr Muhammad Noor Abdul Aziz said educators can always share best practices in educating children so that a growth mindset is put in place.

“With the kind of learners we have now, severe punishment and caning no longer work.

“We must adopt a more flexible way of disciplining them with a give-and-take attitude,” he said.

Agreeing, Sawittri said emphasising a growth mindset would enable educators to reconfigure how they think about the way children learn and how to address undesirable behaviours.

According to Prof Ng, a growth mindset is about focusing on progress, and behaving in ways that contribute to clear and measurable objectives.

“This includes learning about how behaviours can be modified, enhanced or discouraged by using evidence-based methods, rather than personal beliefs in how development or progress can be made,” he said, adding that growth involves problem-solving and being resourceful in seeking solutions.

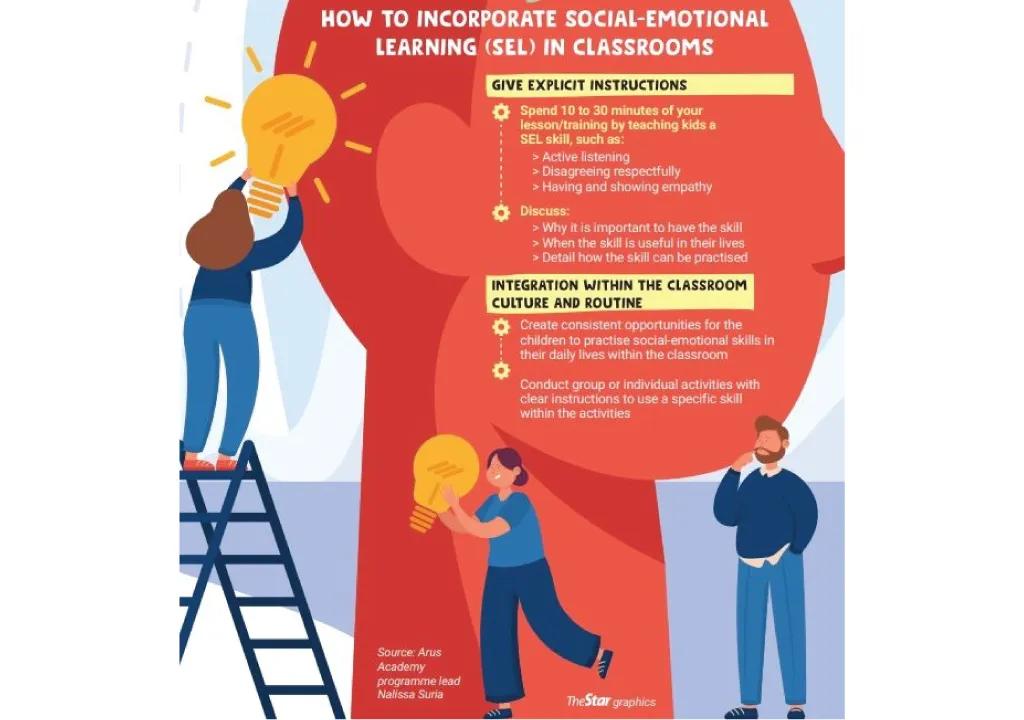

Social-emotional learning (SEL)

“All these physical and mental abuse cases we see happening is directly caused by a lack of SEL skills,” said Khadijah.

While the idea of SEL is not new, there is hardly any emphasis and implementation happening among educators nowadays, she added.

“As educators, we have insufficient exposure to these skills so maybe there is a need for an SEL course,” she added.

The Covid-19 pandemic, she said, forced many people into social isolation.

“It made me realise that it is important to not just focus on academics, but also the physical and psychological well-being of students. When you teach, care should come before content. Spend 20 to 30 minutes to talk about your child’s psychological well-being because you never know what he or she is going through. It’s good to show them empathy.”

Students, she said, tend to be more accepting when adults listen to them and that is exactly what is lacking in many educators today.

“This is why we are seeing cases of physical and emotional abuse by teachers, coaches and parents.”

Indeed, physical and mental violence should never be used as a tool for teaching.

Instead, the focus should be on creating a safe and positive learning environment for children to develop skills and values needed for them to succeed academically and in life.

Educators must remember that they have the power to make a difference and to change society for the better. After all, education, in the words of Nelson Mandela, is the most powerful weapon to change the world.

THE VIEWS

Aggression and corporal punishment can never result in desired behaviours from children. If anything, they can lead to increased aggression among the young. When children are physically punished, they learn that violence is an acceptable way to resolve conflicts, leading to increased aggression in the future. This cycle of aggression can then perpetuate itself, creating a negative school culture where conflicts are not effectively resolved and discipline is meted out through physical or verbal abuse. I cannot begin to imagine the risk of abuse that comes with corporal punishment. Such physical acts can quickly escalate into abuse if the teacher or administrator administering the punishment loses control. This can lead to serious legal and ethical concerns, particularly if the punishment causes hurt or violates the child’s human rights. The most important thing to remember is that the child will face negative physical and emotional consequences that will scar them for life. Children who are subjected to corporal punishment may experience physical harm such as bruises, cuts and even broken bones. Such punishment can even lead to emotional trauma, anxiety and low self-esteem that could follow them into adulthood. We must come up with alternative disciplinary strategies such as positive reinforcement, behaviour modification and conflict resolution. These methods can promote positive behaviour and create a more positive school culture, where children feel safe, respected and valued.

This article was first published in The Star, 26 March 2023.